Whenever I meet someone who’s got a really cool job, who runs a thriving business, or who has completed an amazing project, I always want to know: “How did you do that?”

I’m always curious to hear the “behind-the-scenes story”—who they emailed, what they said, how they got their first client, how they got their foot in the door—the exact steps that they took to achieve their goal.

HOW DID YOU DO THAT? is an interview series where we get to hear the REAL story behind someone’s success—not the polished, neat and tidy version.

To see a complete list of all the interviews that have been completed to date, head over here.

Name: Rachael Soroka

Location: Garden Valley, California

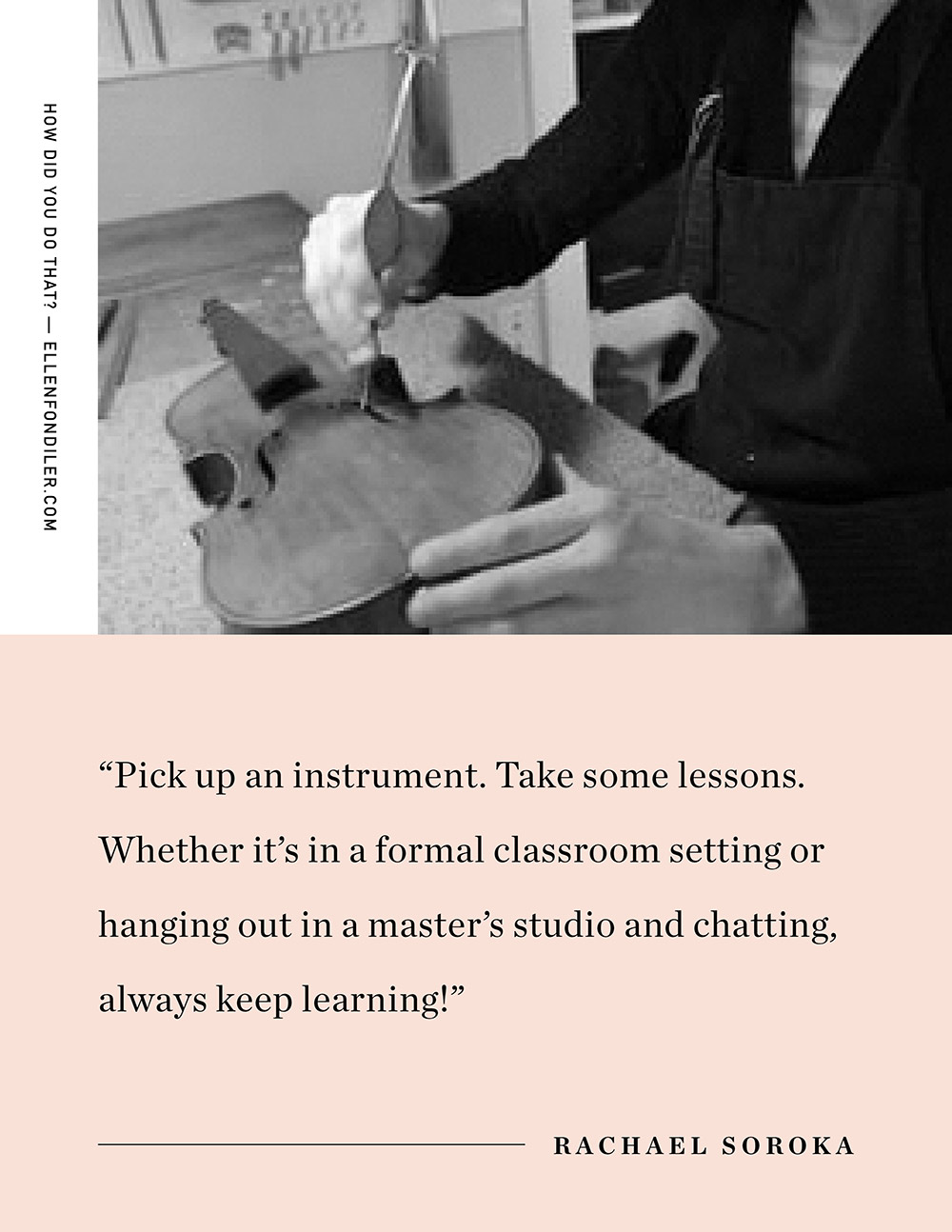

Profession: Owner of Soroka Violins, a violin repair shop

You run a violin repair shop. What an unusual and fascinating career! How did you find your way into this work? Did you play violin as a kid? Did you study music in college? Have you always been interested in taking things apart and putting them back together? How did this happen?

I started playing the violin when I was eight, and my mom dug my great-grandpa’s old fiddle out of grandpa’s attic and we took it to a violin shop to have it fixed up.

I was totally smitten with the shop. It was in Cleveland in an old burned-out industrial part of town in a decrepit reclaimed factory building. The elevator had a human operator! The ceilings were twenty feet tall, and the huge windows looked out over Lake Erie. The workshop was a treasure-trove—wood and violin parts in little cubbies stacked up and piled up and bits stuck in here and there, surrounding an old wooden workbench packed with every kind of blade and hand tool imaginable.

The violin maker, Peter Horn, was a gentleman in his sixties who chain-smoked cigarettes and had a thick German accent. I loved going to his shop! I remember asking him how he got to be a violin maker, and he told me that he studied at the violin making school in Marneukirchen, Germany.

I didn’t think I could ever do that, so I put the idea of being a violin maker myself out of my mind. Until one summer in college when I was working at Pinewoods Camp, a folk music and dance camp for adults near Plymouth, Massachusetts. There was a workshop there that I was allowed to use, and in my free time I tried to make a violin, just for fun, because I had found an old 19th century manual in the local library. Being a folk music camp, lots of fiddlers came through and one of them was a violin maker! He told me that there were schools in America, too, and that some people just learned by apprenticeship. That was enough to launch me!

I dropped out of college that next semester and walked back into Peter Horn’s shop. I asked to be his apprentice. He looked at me like I was crazy and said that usually people paid him to teach them… and I certainly didn’t have any money. But he was a really social and sweet person, and sitting at the workbench can be a pretty solitary activity. So I stood around and chatted with him most of that day, and at the end I asked if I could come back and chat some more. “Of course!” he said. And that’s how I sneaked into an apprenticeship. I got a job waiting tables, and on all my days off, I went to Cleveland and stood behind Peter Horn and watched and asked questions, and listened to polka music on the radio, and breathed second-hand smoke. It was wonderful. After doing that for about a year, he hired me because he said I knew too much to be helping him out for free. And so I had my foot in the door and a traditional violin maker’s apprenticeship on my résumé.

Wow! That’s an incredible story. Someone needs to turn your life into an Oscar-winning movie called The Violin Maker’s Apprentice, or something like that! Take us back to the early days of your business. How did it feel to open your own shop? Did you have customers right away? Or did things feel “quiet” and “empty” at first? Did you feel excited? Nervous? Both?

It’s funny, I don’t remember being nervous when I left the safety of a salary and went to work for myself. I took a part-time administrative job for a local business as a buffer, and started working on violins from home. I had contract work from other violin shops right away—the shop I had been working in sent me work, and then more shops found me and started sending me work. And then local people starting finding me and coming in, and they would tell people so more people would come… It has been a steady and pretty stress-free process.

Have you ever had a customer who made you feel a little star-struck—like a famous musician, composer, or conductor? Did you start babbling with excitement, or were you able to keep your cool?

I’m not that prone to being star-struck by people, and there’s something about a person who thinks they are a star that pretty much turns me off. We are all on the road of mastery, and some people are a little farther along is all.

But when I have felt star-struck is seeing old instruments made by the masters who’ve been dead and gone for centuries already. I’ve worked on instruments that are 300 years old! Just holding one of those old beautiful masterpieces is a thrill—I can feel the thousands and thousands of hours of music that have been played, the generations of humans who have come and gone using that instrument as the tool to do the work of the muse, and the artistry and dedication of a lifetime that the violin maker put into that wood so many years ago. It’s really breathtaking.

Has there ever been a moment in your career where you felt really discouraged—or a moment when you considered shutting down your business? What happened, how did you feel, and how did you get yourself through that moment?

The worst time was when I was working for a violin shop in Vermont. The two men who owned the shop were amazing—they both played for the symphony, and they were both really skilled in the shop in two different ways: one knew about identifying and valuing instruments and all the business aspects of running the shop, and the other was the violin maker. I learned so much from both of them!

But after a few years there, they sold the shop, and the folks who bought it and I just did not click. At all. They were business people and didn’t know much about violins, and so they made me “head of the repair shop,” which I did not feel qualified for, and I really wanted to keep learning from someone out ahead of me. I felt really lonely and the “suits” kept pushing me to push the other repair-people in the business who were now working under me to work harder and faster, but they kept hiring totally unskilled and inexperienced people who weren’t capable of doing better or faster work. It was so awful.

So I sent résumé s around to be best shops in the country, looking for a new job, and I ended up in a world-famous shop in San Francisco working for a violin maker who had studied as a young man at the violin making school in Germany, and then came to the USA to work for the best shop in the country at the time under the “father of modern violin making.” So, I was back to learning and growing under this master’s feedback. Problem solved.

What’s the most rewarding part of your work—the moments that make you think, “Wow, I’m so grateful this is my job”?

I love to learn and grow. And the best part of being a violin maker is that one can never actually master anything. As soon as your hands get good at something, your eye gets better too and pretty soon the eye is pointing out how your hands can improve. Then your hands catch back up and the process repeats. In addition, there are many ways to skin a cat and you can always learn from other people and try new approaches and new materials.

I imagine that restoring violins will keep me intrigued until I die. So far, I’m still fascinated, and it’s been 17 years!

3 Things

If someone wants to start a career building and repairing musical instruments, like you, what are the first 3 things they should do?

1. Make art.

Paintings and sculptures, especially. This will train your eye and train your ability to see something in your mind and then make it happen in the physical realm.

2. Learn to work with wood.

Learn which tools to use and when. Learn to sharpen blades until you can use them as razors. Learn how wood behaves. To get started, sign up for a general woodworking class at a local community college—especially if the class uses hand tools rather than machines.

3. Play music.

Pick up an instrument. Take some lessons. Whether it’s in a formal classroom setting or hanging out in a master’s studio and chatting, always keep learning!

ONE MORE THING…

Do you have “one more quick question” that you’d like to ask Rachael? Email me and tell me what you want to know! I might choose your question for my ONE MORE THING… Podcast (Coming soon!!!)

YOUR #1 CAREER GOAL: ACHIEVED

Do you need some encouragement to help you achieve a big, daunting career goal? Would you like to have a career coach/strategist in your corner—feeding you ideas that you’d never considered before, helping you figure out who to contact, and what to say, and checking in to make sure you don’t procrastinate? If so… click here to find out how we can work together. I’d love to coach you!

![]()